The Winter's Tale

The Winter's Tale is a play by William Shakespeare, originally published in the First Folio of 1623. Although it was grouped among the comedies,[1] some modern editors have relabeled the play as one of Shakespeare's late romances. Some critics, among them W. W. Lawrence,[2] consider it to be one of Shakespeare's "problem plays", because the first three acts are filled with intense psychological drama, while the last two acts are comedic and supply a happy ending.

Nevertheless, the play has been intermittently popular, revived in productions in various forms and adaptations by some of the leading theatre practitioners in Shakespearean performance history, beginning after a long interval with David Garrick in his adaptation called Florizel and Perdita (first performed in 1754 and published in 1756. The Winter's Tale was revived again in the 19th century, when the third "pastoral" act was widely popular). In the second half of the 20th century The Winter's Tale in its entirety, and drawn largely from the First Folio text, was often performed, with varying degrees of success.

Contents |

Sources

The main plot of The Winter's Tale is taken from Robert Greene's pastoral romance Pandosto, published in 1588. Shakespeare's changes to the plot are uncharacteristically slight, especially in light of the romance's undramatic nature, and Shakespeare's fidelity to it gives The Winter's Tale its most distinctive feature: the sixteen-year gap between the third and fourth acts.

There are minor changes in names, places, and minor plot details, but the largest changes lie in the survival and reconciliation of Hermione and Leontes (Greene's Pandosto) at the end of the play. The character equivalent to Hermione in Pandosto dies after being accused of adultery, while Leontes' equivalent looks back upon his deeds (including an incestuous fondness for his daughter) and slays himself. The survival of Hermione, while presumably intended to create the last scene's coup de théâtre involving the statue, creates a distinctive thematic divergence from Pandosto. Greene follows the usual ethos of Hellenistic romance, in which the return of a lost prince or princess restores order and provides a sense of closure that evokes Providence's control. Shakespeare, by contrast, sets in the foreground the restoration of the older, indeed aged, generation, in the reunion of Leontes and Hermione. Leontes not only lives, but seems to insist on the happy ending of the play.

It has been suggested that the use of a pastoral romance from the 1590s indicates that at the end of his career, Shakespeare felt a renewed interest in the dramatic contexts of his youth. Minor influences also suggest such an interest. As in Pericles, he uses a chorus to advance the action in the manner of the naive dramatic tradition; the use of a bear in the scene on the Bohemian seashore is almost certainly indebted to Mucedorus,[3] a chivalric romance revived at court around 1610.

Eric Ives, the biographer of Anne Boleyn (1986),[4] believes that the play is really a parallel of the fall of the queen, who was beheaded on false charges of adultery on the orders of her husband Henry VIII in 1536. There are numerous parallels between the two stories – including the fact that one of Henry's closest friends, Sir Henry Norreys, was beheaded as one of Anne's supposed lovers and he refused to confess in order to save his life – claiming that everyone knew the Queen was innocent. If this theory is followed then Perdita becomes a dramatic presentation of Anne's only daughter, Queen Elizabeth I.

Date and text

The play was not published until the First Folio of 1623. In spite of tentative early datings (see below), most critics believe the play is one of Shakespeare's later works, possibly written in 1610 or 1611.[5] A 1611 date is suggested by an apparent connection with Ben Jonson's Masque of Oberon, performed at Court 1 January 1611, in which appears a dance of ten or twelve satyrs; The Winter's Tale includes a dance of twelve satyrs, and the servant announcing their entry says "one three of them, by their own report, sir, hath danc'd before the King." (IV.iv.337-38). Arden Shakespeare editor J.H.P. Pafford found that "the language, style, and spirit of the play all point to a late date. The tangled speech, the packed sentences, speeches which begin and end in the middle of a line, and the high percentage of light and weak endings are all marks of Shakespeare's writing at the end of his career. But of more importance than a verse test is the similarity of the last plays in spirit and themes."[6]

In the late 18th century, Edmund Malone suggested that a "book" listed in the Stationers' Register on May 22, 1594, under the title "a Wynters nightes pastime" might have been Shakespeare's, though no copy of it is known.[7] In 1933, Dr. Samuel A. Tannenbaum wrote that Malone subsequently "seems to have assigned it to 1604; later still, to 1613; and finally he settled on 1610–11. Hunter assigned it to about 1605."[8]

Performance

The earliest recorded performance of the play was recorded by Simon Forman, the Elizabethan "figure caster" or astrologer, who noted in his journal on 11 May 1611 that he saw The Winter's Tale at the Globe playhouse. The play was then performed in front of King James at Court on 5 November 1611. The play was also acted at Whitehall during the festivities preceding Princess Elizabeth's marriage to Frederick V, Elector Palatine, on 14 February 1613. Later Court performances occurred on 7 April 1618, 18 January 1623, and 16 January 1634.[9]

The Winter's Tale was not revived during the Restoration, unlike many other Shakespearean plays. It was performed in 1741 at Goodman's Fields Theatre and in 1742 at Covent Garden. Adaptations, titled The Sheep-Shearing and Florizal and Perdita, were acted at Covent Garden in 1754 and at Drury Lane in 1756.[10]

One of the most famous modern productions was staged by Peter Brook in London in 1951 and starred John Gielgud as Leontes. Other notable stagings featured John Philip Kemble in 1811, Samuel Phelps in 1845, and Charles Kean in an 1856 production that was famous for its elaborate sets and costumes. Johnston Forbes-Robertson played Leontes memorably in 1887, and Herbert Beerbohm Tree took on the role in 1906. The longest-running Broadway production[11] the longest one starred Henry Daniell and Jessie Royce Landis, and ran for 39 performances in 1946. In 1980, David Jones (director), former Associate Artistic Director of the Royal Shakespeare Company chose to launch his new theatre company at the Brooklyn Academy of Music (BAM) with The Winter's Tale starring Brian Murray supported by Jones' new company at BAM [12] In 1983, the Riverside Shakespeare Company mounted a production based on the First Folio text at The Shakespeare Center in Manhattan. In 1993 Adrian Noble won a Globe Award for Best Director for his Royal Shakespeare Company adaptation, which then was successfully brought to the Brooklyn Academy of Music in 1994. [13]

In 2009, three separate productions were staged. Sam Mendes inaugurated his transatlantic "Bridge Project" directing The Winter's Tale with a cast featuring Simon Russell Beale (Leontes), Rebecca Hall (Hermione), Ethan Hawke (Autolycus) and Sinéad Cusack (Paulina). The Royal Shakespeare Company[14] and Theatre Delicatessen[15] also staged productions of The Winter's Tale in 2009. The play is in the repertory of the Stratford Festival of Canada and was seen at the New York Shakespeare Festival, Central Park, in 2010.

Characters

- Leontes – The King of Sicilia, and the childhood friend of the Bohemian King Polixenes. He is gripped by jealous fantasies, which convince him that Polixenes has been having an affair with his wife, Hermione; his jealousy leads to the destruction of his family.

- Hermione – The virtuous and beautiful Queen of Sicilia. Falsely accused of infidelity by her husband, Leontes, she apparently dies of grief just after being vindicated by the Oracle of Delphos, but is restored to life at the play's close.

- Perdita – The daughter of Leontes and Hermione. Because her father believes her to be illegitimate, she is abandoned as a baby on the coast of Bohemia, and brought up by a Shepherd. Unaware of her royal lineage, she falls in love with the Bohemian Prince Florizel.

- Polixenes – The King of Bohemia, and Leontes's boyhood friend. He is falsely accused of having an affair with Leontes's wife, and barely escapes Sicilia with his life. Much later in life, he sees his only son fall in love with a lovely Shepherd's daughter—who is, in fact, a Sicilian princess.

- Florizel – Polixenes's only son and heir; he falls in love with Perdita, unaware of her royal ancestry, and defies his father by eloping with her.

- Camillo – An honest Sicilian nobleman, he refuses to follow Leontes's order to poison Polixenes, deciding instead to flee Sicily and enter the Bohemian King's service.

- Paulina – A noblewoman of Sicilia, she is fierce in her defense of Hermione's virtue, and unrelenting in her condemnation of Leontes after Hermione's death. She is also the agent of the (apparently) dead Queen's resurrection.

- Autolycus – A roguish peddler, vagabond, and pickpocket; he steals the Clown's purse and does a great deal of pilfering at the Shepherds' sheepshearing, but ends by assisting in Perdita and Florizel's escape.

- Shepherd – An old and honorable sheep-tender, he finds Perdita as a baby and raises her as his own daughter.

- Antigonus – Paulina's husband, and also a loyal defender of Hermione. He is given the unfortunate task of abandoning the baby Perdita on the Bohemian coast. He inevitably meets his doom (as ascribed to him through a dream) upon abandoning the newborn baby on the island.

- Clown – The Shepherd's buffoonish son, and Perdita's adopted brother.

- Mamillius – The young prince of Sicilia, Leontes and Hermione's son. He dies, perhaps of grief, after his father wrongly imprisons his mother.

- Cleomenes – A lord of Sicilia, sent to Delphos to ask the Oracle about Hermione's guilt.

- Dion – A Sicilian lord, he accompanies Cleomenes to Delphos.

- Emilia – One of Hermione's ladies-in-waiting.

- Archidamus – A lord of Bohemia.

- Mopsa – A 'loose' shepherdess enthralled with Clown.

- Dorcas – Another 'loose' shepherdess fighting over Clown

- The Bear

Synopsis

Following a brief setup scene the play begins with the appearance of two childhood friends: Leontes, King of Sicilia, and Polixenes, the King of Bohemia. Polixenes is visiting the kingdom of Sicilia, and is enjoying catching up with his old friend. However, after nine months, Polixenes yearns to return to his own kingdom to tend to affairs and see his son. Leontes desperately attempts to get Polixenes to stay longer, but is unsuccessful. Leontes then sends his wife, Queen Hermione, to try to persuade Polixenes. Hermione agrees and with three short speeches is successful. Leontes is puzzled as to how Hermione convinced Polixenes so easily, and is suddenly consumed with an insane paranoia that his pregnant wife has been having an affair with Polixenes and that the child is a bastard. Leontes orders Camillo, a Sicilian Lord, to poison Polixenes.

When Camillo instead warns Polixenes and they both flee to Bohemia, Leontes arrests Hermione on charges of adultery and conspiracy against his life. Paulina, a woman of the court and an ardent friend to Hermione, attempts to visit Hermione but must settle with seeing her handmaid, who reports Hermione has prematurely given birth to a daughter in prison. Paulina, hoping the sight of his child will convince him where words have not, takes the child to Leontes. Leontes angrily dismisses all attempts to convince him he is wrong and he believes Antigonus, a Sicilian courtier and Paulina's husband, has conspired against him alongside Paulina. Paulina having gone, Leontes considers killing this child—which he believes to be the bastard of Polixenes and Hermione—before ordering Antigonus, instead, to abandon the infant far away.

At her trial for treason, Hermione delivers a heart-rending speech that fails to move Leontes. A report from the Oracle on the Isle of Delphos pronounces her innocent, but Leontes defies the oracle. But he then immediately receives word that his young son, Mamillius, has died of grief, a fulfillment of another of the Oracle's prophecies. Hermione faints and is reported to have died. Leontes laments his poor judgment and promises to grieve for his dead wife and son every day for the rest of his life.

Antigonus, unaware of Leontes' change of heart, follows Leontes' earlier instructions to abandon Hermione's newborn daughter on the seacoast of Bohemia. Antigonus recalls a vision the night before of Hermione, who told him to name the child "Perdita" (Latin: 'lost'). He wishes to take pity on the child, but Antigonus is then suddenly pursued and eaten by a bear. Fortunately, Perdita is rescued by a shepherd and his simpleton son also known as "Clown." There is a large amount of money with the baby and the shepherd is now very rich.

Time enters and announces the passage of sixteen years. Leontes has spent the sixteen years mourning his wife and children. In Bohemia, Polixenes and Camillo become aware that Florizel (Polixenes' son) has become infatuated with a shepherdess. They attend a sheep-shearing festival (in disguise) and confirm that the young Prince Florizel plans to marry a shepherd's beautiful young daughter (Perdita, who knows nothing of her royal heritage). Polixenes objects to the marriage and threatens the young couple. Quickly, the lovers flee to Sicilia with the help of Camillo, and Polixenes pursues them. Eventually, with a bit of help from a comical rogue/pickpocket named Autolycus, Perdita's heritage is revealed and she reunites with her father Leontes. The kings are reconciled and both approve of Florizel and Perdita's marriage. They all go to visit a statue of Hermione kept by Paulina. Miraculously, the statue comes to life and speaks, appearing to be the real Hermione, who went into hiding to await the fulfilment of the oracle's prophecy and be reunited with her daughter.

Debates

The statue

While the language Paulina uses in the final scene evokes the sense of a magical ritual, one often-overlooked moment in 5.2 shows the far likelier case – that Paulina hid Hermione at a remote location to protect her from Leontes' wrath and that the re-animation of Hermione does not derive from any magic. When the Third Gentleman announces that the members of the court have gone to Paulina's dwelling to see the statue, the Second Gentleman offers this exposition: "I thought she had some great matter there in hand, for she [Paulina] hath privately twice or thrice a day, ever since the death of Hermione, visited that removed house" (5.2.104–106). What's more, Leontes is surprised that the statue is wrinkled, unlike the Hermione he remembers. Paulina answers his concern by claiming that the age-progression attests to the "carver's excellence", which makes her look "as [if] she lived now." Hermione later asserts that her desire to see her daughter allowed her to endure 16 years of separation: "thou shalt hear that I, / Knowing by Paulina that the oracle / Gave hope thou wast in being, have preserved / Myself to see the issue" (5.3.126–129)

However, the action of 3.2 calls into question the "rational" explanation that Hermione was spirited away and sequestered for 16 years. Hermione swoons upon the news of Mamilius' death, and is rushed from the room. Paulina returns after a short monologue from Leontes, bearing the news of Hermione's death. After some discussion, Leontes demands to be led toward the bodies of his wife and son: "Prithee, bring me / To the dead bodies of my queen and son: / One grave shall be for both: upon them shall / The causes of their death appear, unto / Our shame perpetual" (3.2) Paulina seems convinced of Hermione's death, and Leontes order to visit both bodies and see them interred is never called into question by later events in the play.

Such contradictory (or vague) evidence renders any definitive answer about the nature of the statue elusive.

The seacoast of Bohemia

Shakespeare's fellow playwright Ben Jonson ridiculed the presence in the play of a seacoast and a desert in Bohemia, since the kingdom of Bohemia (which roughly corresponds to the modern-day Czech Republic) had neither a coast (being landlocked) nor a desert.[16][17] Shakespeare's source, the romance Pandosto by Robert Greene, had the shipwreck instead take place on the Sicilian coast.[18] However, in the 13th century under Ottokar II of Bohemia the kingdom of Bohemia did stretch to the Adriatic, and it was, in fact, possible to sail from a kingdom of Sicily to the seacoast of Bohemia.[19] Moreover, in Shakespeare's time, Rudolph, king of Bohemia, also was Holy Roman Emperor and ruled over the Adriatic coast neighboring the Venetian Republic, a fact noted by some Oxfordian scholars [See: authorship], who find it significant that the Earl of Oxford was traveling in the Adriatic region during this brief span of time. Jonathan Bate offers the simple explanation that the court of King James was politically allied with that of Rudolph, and the characters and dramatic roles of the rulers of Sicily and Bohemia were reversed for reasons of political sensitivity. Indeed, had not Shakespeare made this departure from his sources the play's performance at the wedding celebrations of Princess Elizabeth, a future queen of Bohemia, could not have taken place.[20]

In 1891, Edmund O. von Lippmann pointed out that "Bohemia" was also a rare name for Apulia in southern Italy.[21] More influential was Thomas Hanmer's 1744 argument that Bohemia is a printed error for Bithynia, an ancient nation in Asia Minor;[22] this theory was adopted in Charles Kean's influential 19th century production of the play, which featured a resplendent Bythinian court.

The pastoral genre is not known for precise verisimilitude, and, like the assortment of mixed references to ancient religion and contemporary religious figures and customs, this possible inaccuracy may have been included to underscore the play's fantastical and chimeric quality. As Andrew Gurr puts it, Bohemia may have been given a seacoast "to flout geographical realism, and to underline the unreality of place in the play".[23]

Another theory explaining the existence of the seacoast in Bohemia is suggested in Shakespeare's chosen title of the play. A winter's tale is something associated with parents telling children stories of legends around a fireside: by using this title it is implying to the audience not to take these details too seriously.[24]

The Isle of Delphos

Likewise, Shakespeare's apparent mistake of placing the Oracle of Delphi on a small island has been used as evidence of Shakespeare's limited education. However, Shakespeare again copied this locale directly from "Pandosto". Moreover, the erudite Robert Greene was not in error, as the Isle of Delphos does not refer to Delphi, but to the Cycladic island of Delos, the mythical birth place of Apollo, which from the 15th to the late 17th century in England was known as "Delphos".[25] Greene's source for an Apollonian oracle on this island likely was the Aeneid, in which Virgil wrote that Priam consulted the Oracle of Delos before the outbreak of the Trojan War and that Aeneas after escaping from Troy consulted the same Delian oracle regarding his future.[26]

The Bear

The play contains one of the most famous Shakespearean stage directions: Exit, pursued by a bear, presaging the offstage death of Antigonus. It is not known whether Shakespeare used a real bear from the London bear-pits,[27] or an actor in bear costume. The Royal Shakespeare Company, in one production of this play, used a large sheet of silk which moved and created shapes, to symbolise both the bear and the gale in which Antigonus is travelling.

Dildos

One comic moment in the play deals with a servant not realizing that poetry featuring references to dildos is vulgar, presumably from not knowing what the word means. This play and Ben Jonson's play The Alchemist (1610) are typically cited as the first usage of the word in publication.[28] The Alchemist was printed first, but the debate about the date of the play's composition makes it unclear which was the first scripted use of the word, which is much older.[29]

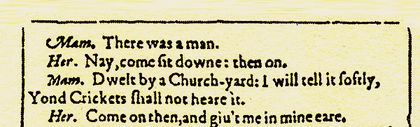

Who is "A man ... Dwelt by a Church-yard"?

What, exactly is the "winter's tale" referred to in the title? One possible answer was suggested in a 1983 production of the uncut First Folio script of The Winter's Tale by the Riverside Shakespeare Company at The Shakespeare Center, in which the director, W. Stuart McDowell, posited an answer to who the man is in the story told by Mamillius, and hence what, exactly, is the "winter's tale". The production, which combined modern (Grace Kelly's Monaco) and historical (pastoral 18th century England) periods, staged a magical transformation when Mamillius begins to recount the "winter's tale" to his mother, Hermione. According the program note, the concept arose from the moment in the First Folio text when Mamillius is asked to "tell's a Tale", to which the boy responds with "There was a man ... dwelt by a Church-yard ..." According to the Riverside program, McDowell's interpretation posited that these eight words – the entirety of "A sad Tale" that is "best for Winter" – are nothing less than a prophecy concerning Leontes, who would some day dwell by a graveyard (i.e., church-yard), mourning the passing of Hermione and Mamillius for whose deaths he had himself to blame.[31]

Film/Television adaptions

There have been two film versions, one silent version in 1910[32] and a 1967 version starring Laurence Harvey as Leontes.[33]

An "orthodox" BBC production was televised in 1981. It was produced by Jonathan Miller, directed by Jane Howell and starred Robert Stephens as Polixenes and Jeremy Kemp as Leontes.[34] There have been several other BBC versions televised as well.

References

- ↑ WT comes last, following Twelfth Night which uncharacteristically ends with a blank recto page, suggesting to Arden editor J.H.P. Pafford there was some hesitation as to where WT belonged at the time of printing the Folio. (J.H.P. Pafford, ed. The Winter's Tale (Arden Shakespeare) 3rd ed. 1933:xv–xvii.)

- ↑ Lawrence, 9–13,

- ↑ C. F. Tucker Brooke, The Shakespeare Apocrypha, Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1908; pp. 103–26.

- ↑ Ives, The Life and Death of Anne Boleyn 2004:421: in spite of other scholars' rejection of any parallels between Henry VIII and Leontes, asserts "the parallels are there", noting his article "Shakespeare and History: divergencies and agreements", in Shakespeare Survey 38 (1985:19–35), p 24f.

- ↑ F. E. Halliday, A Shakespeare Companion 1564–1964, Baltimore, Penguin, 1964; p. 532.

- ↑ Pafford, J.H.P., ed. "Introduction", The Winter's Tale Arden Shakespeare 2nd. series (1963, 1999), xxiii.

- ↑ Malone, Edmund. "An Attempt to Ascertain the Order in which the Plays Attributed to Shakspeare Were Written," The Plays and Poems of William Shakespeare in Ten Volumes. Eds. Samuel Johnson and George Steevens. 2nd ed. London, 1778, Vol. I: 269-346; 285.

- ↑ Tannenbaum, "The Forman Notes", Shakespearean Scraps, 1933

- ↑ All dates new style.

- ↑ Halliday, pp. 532–3.

- ↑ Four previous productions in New York, the earliest that of 1795 are noted in the Internet Broasdway Database; The Winter's Tale has not played on Broadway since 1946.

- ↑ "Brooklyn Bets on Rep", T. E. Kalem, Time Magazine, 3 March 1980

- ↑ "Critics Notebook", Ben Brantley, The New York Times, 22 April 1994.

- ↑ RSC listing

- ↑ The Stage review of [Theatre Delicatessen]'s The Winter's Tale

- ↑ Wylie, Laura J., ed (1912). The Winter's Tale. New York: Macmillan. p. 147. OCLC 2365500. "Shakespeare follows Greene in giving Bohemia a seacoast, an error that has provoked the discussion of critics from Ben Jonson on."

- ↑ Ben Jonson, 'Conversations with Drummond of Hawthornden', in Herford and Simpson, ed. Ben Jonson, vol. 1, p. 139.

- ↑ Greene's 'Pandosto' or 'Dorastus and Fawnia': being the original of Shakespeare's 'Winter's tale', P.G. Thomas, editor. Oxford University Press, 1907

- ↑ See J.H. Pafford, ed. The Winter's Tale, Arden Edition, 1962, p. 66

- ↑ Bate, Jonathan (2008). "Shakespeare and Jacobean Geopolitics". Soul of the Age. London: Viking. p. 305. ISBN 978-0-670-91482-1.

- ↑ Edmund O. von Lippmann, 'Shakespeare's Ignorance?', New Review 4 (1891), 250–4.

- ↑ Thomas Hanmer, The Works of Shakespeare (Oxford, 1743–4), vol. 2.

- ↑ Andrew Gurr, 'The Bear, the Statue, and Hysteria in The Winter's Tale, Shakespeare Quarterly 34 (1983), p. 422.

- ↑ See C.H. Herford, ed. The Winter's Tale, The Warwick Shakespeare edition, p.xv.

- ↑ Terence Spencer, Shakespeare's Isle of Delphos, The Modern Language Review, Vol. 47, No. 2 (Apr., 1952), pp. 199–202.

- ↑ Virgil, Aeneid, In. 73–101

- ↑ The main bear-garden in London was the Paris Garden at Southwark, near the Globe Theatre.

- ↑ See, for instance, "dildo1". OED Online (2nd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. 1989. http://dictionary.oed.com/cgi/entry/50064101. Retrieved 21 April 2009, which cites Jonson's 1610 edition of The Alchemist ("Here I find ... The seeling fill'd with poesies of the candle: And Madame, with a Dildo, writ o' the walls.": Act V, scene iii) and Shakespeare's The Winter's Tale (dated 1611, "He has the prettiest Loue-songs for Maids ... with such delicate burthens of Dildo's and Fadings.": Act IV, scene iv).

- ↑ The first reference in the Oxford English Dictionary is Thomas Nashe's Choise of Valentines or the Merie Ballad of Nash his Dildo (c. 1593); in the 1899 edition, the following sentence appears: "Curse Eunuke dilldo, senceless counterfet."

- ↑ Page 282 from the First Folio of Shakespeare's The Winter's Tale, reproduced on the program cover of the Riverside Shakespeare Company's production of the play, 25 February 1983.

- ↑ Seymour Isenberg, "Sunny Winter", in The New York Shakespeare Society Bulletin, (Dr. Bernard Beckerman, Chairman; Columbia University) March 1983, p. 25.

- ↑ The Winter's Tale (1910)

- ↑ The Winter's Tale (1968)

- ↑ "The Winter's Tale (1981, TV)". IMDB. http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0081761/fullcredits. Retrieved 22 January 2010.

Sources

- Brooke, C. F. Tucker. 1908. The Shakespeare Apocrypha, Oxford, Clarendon press, 1908; pp. 103–26.

- Gurr, Andrew. 1983. "The Bear, the Statue, and Hysteria in The Winter's Tale", Shakespeare Quarterly 34 (1983), p. 422.

- Halliday, F. E. 1964. A Shakespeare Companion 1564–1964, Baltimore, Penguin, 1964; p. 532.

- Hanmer, Thomas. 1743. The Works of Shakespeare (Oxford, 1743–4), vol. 2.

- Isenberg, Seymour. 1983. "Sunny Winter", The New York Shakespeare Society Bulletin, (Dr. Bernard Beckerman, Chairman; Columbia University) March 1983, pp. 25–26.

- Jonson, Ben. "Conversations with Drummond of Hawthornden", in Herford and Simpson, ed. Ben Jonson, vol. 1, p. 139.

- Kalem, T. E. 1980. "Brooklyn Bets on Rep", Time Magazine, March 3, 1980.

- Von Lippmann, Edmund O. 1891. "Shakespeare's Ignorance?", New Review 4 (1891), 250–4.

- McDowell, W. Stuart. 1983. Director's note in the program for the Riverside Shakespeare Company production of The Winter's Tale, New York City, February 25, 1983.

- Pafford, John Henry Pyle. 1962, ed. The Winter's Tale, Arden Edition, 1962, p. 66.

- Tannenbaum, Dr. Samuel A. 1933. " Shakespearean Scraps", chapter: "The Forman Notes" (1933).

- Verzella, Massimo, "Iconografia femminile in The Winter's Tale", Merope, XII, 31 (settembre 2001), pp. 49–68;

- Verzella, Massimo,"Petrarchism and anti-Petrarchism in The Winter's Tale" in Merope, numero speciale dedicato agli Studi di Shakespeare in Italia, a cura di Michael Hattaway e Clara Mucci, XVII, 46–47 (Set. 2005– Gen. 2006), pp. 161–179.

External links

- The Winters Tale—HTML version of this title.

- Winter's Tale—Full text HTML of Shakespeare's play.

- Winters Tale—plain vanilla text from Project Gutenberg

- Full text of play

- Shakespeare's Plays at Wikisource

- A thorough (open source) concordance of all of Shakespeare's plays

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||